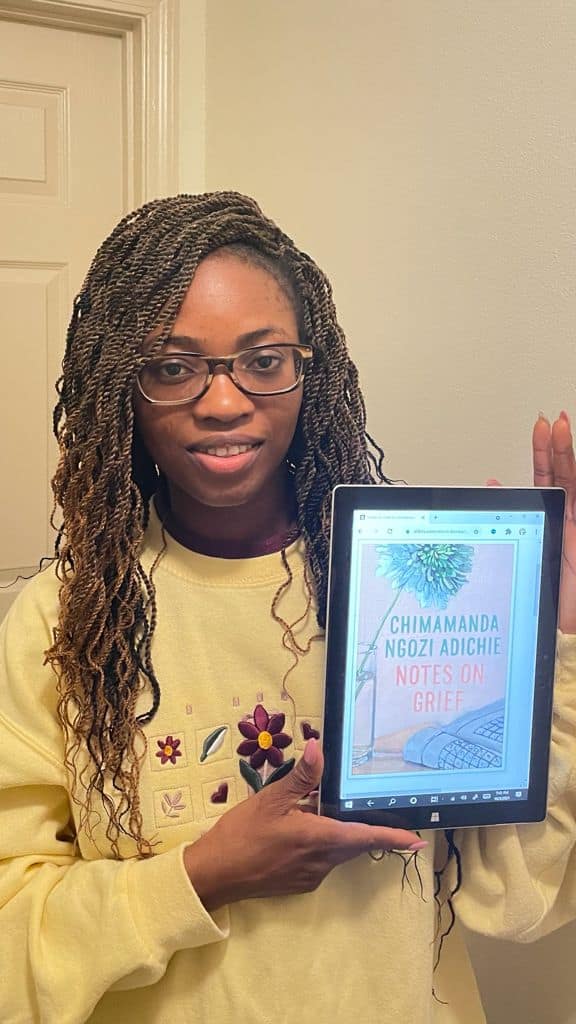

Review of ‘Notes on Grief’ by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

In many Western cultures, particularly Great Britain and in the United States, the grief memoir remains a sought-after genre due to its form of public morning and occasional self-therapy. Here, the bereaved is in search of meaning amid pain or hurt. The kind of pain that comes with the death of a parent, child, sibling, or a loved one. This pain no doubt leaves one bereft of meaning and turns one’s world upside down such that language itself becomes somewhat useless. How can words fulfil its responsibility of giving meaning, meaning to silence, meaning to a shapeless encounter. Emily Dickinson engulfs the effort of language’s attempt to give meaning in her words, “To attempt to speak of what has been, would be impossible. Abyss has no biographer.”

For over two decades, autobiographical writing, talk shows about deep life details, especially memoir of loss has emerged as a notable literary genre, breaking silence by giving voice to loss/grief in a broad and open-minded way. It is noteworthy that grief/loss memoirs are highly relational. Grief remains a reality or experience that tries to annihilate the expressive role of language and boundaries of time such that influential memoirs like Blake Morrison’s And When Did You Last See Your Father? Marion Coutts’s The Iceberg among others grappled with expounding answers to it. It cannot be said affirmatively that the dead is gone or the relationship with them is over. We have our times and experiences with them differently.

Upon losing her father, in her slim and agonized book, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie writes in a poetic form that mirrors her fractured self and produces a style of mourning that is both loving and haunting. Adichie launches into expounding her understanding of grief as brutal form of education. She describes, “you learn how much grief is about language, the failure of language and the grasping for language.” To her, words become wanting such that the show of sympathy from her extended family and friends become counterproductive and somewhat annoying. When she is told that her father lived long (died at 88), she is slightly consoled, but she maintains that “Age is irrelevant in grief; at issue is not how old he was but how loved.” To say that the death of a person means being in a better place is rather presumptuous. “How would you know?” she asks.

In this book, she chastises herself as she recalls her previous ways of consoling grieving friends. She was reminded by a friend of the words she used in her book Half of a Yellow Sun “Grief was the celebration of love, those who could feel real grief were lucky to have loved.” Adichie finds her words “exquisitely painful.”

To understand her pain, Adichie uses her daughter demonstration:

“My four year old daughter says I scared her. She got down on her knees to demonstrate, her small clenched fist rising and falling, and her mimicry makes me see myself as I was: utterly unraveling, screaming and pounding the floor. The news is like a vicious uprooting.”

If you have lost a loved one at any point, you would understand Adichie’s guilt and anger. How she could have averted the illness, taken better care of him or just make it all never happen (the death). This happens while grieving, we keep blaming ourselves about things we could have done that we never did even though death is beyond our power.

To some degree, reflecting on her father’s life gave some form of comfort which is typical while grieving. As a writer, Adichie understands that words are not enough to explain one’s feelings as she writes: “You learn how much grief is about language, the failure of language and the grasping for language.”

Adichie holds that communal mourning is overwhelming (even though solace is feasible in community), but it remains a value in the Igbo society and in Africa. Individuals come visiting, retell stories and write things about the dead in a book. She becomes utterly annoyed and thinks, “Why are you coming into our house to write in that alien notebook? How dare you make this thing true?” For her these acts make it feel real that her father is dead as she prefers to remain in denial. The only word that made sense to Adichie is Ndo, meaning sorry in Igbo.

It is obvious that Adichie wants her dad back; she is saying goodbye, she is saying she is sorry and at the same time saying do not go. All these are possible because writing a grief memoir shows there is an end, just as Jacques Derrida puts it, when you write, you ask for forgiveness.

Literature remains a crucial aspect and plays a reflective role on culture and society as it indirectly offers a therapeutic path to readers. Emphasizing the sociocultural role of literature, Isabel Allende’s memoir addressed to the author’s daughter, Paula, Shapiro (1998) maintained:

Although most psychotherapists read literary works as a means of enriching our own emotional and intellectual lives, we are less likely to read such writing for lessons on how to conduct treatment, yet the work of creative writers, especially their personal narratives or memoirs, can offer extremely useful examples of life story vision and revision as a source of emotional healing. … The explosion of interest in memoirs suggests our own society’s loss of shared stories and the longing to communicate and learn from the insights we and others have gained through self-reflection. Every time I want to explore a new dimension of psychology, I turn to both “literatures,” that is, both the scientific and the literary, for the insights that will shape my understanding. (p. 93)

Notes on Grief remains a piece of art larger than its size, universal in its experience of loss of a loved one, and the struggle to grieve especially during a pandemic when physical meeting is limited.

References

Image excerpts: https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/notes-on-grief-chimamanda-ngozi-adichie/1138792627

Shapiro, E. R. (1998). The healing power of culture stories: What writers can teach psychotherapists. Cultural Diversity and Mental Health, 4(2), 91–101. https://doi.org/10.1037/1099-9809.4.2.91

5 Comments

Saraphina

The pain of losing someone so dear can be a whole hell of trauma. But overtime, my perspective about “death” and the fact that I cannot undo what has been done, helps my healing process when I grief about the loss of a loved one.

However, the worst part is, as human, in as much as I try to keep my cool, my mind will keep flashing back to those beautiful memories I’ve once shared with that person. To crown it all, what makes the pain unbearable is how people would then immediately begin to retell the deeds of the deceased in ‘past tense’. I think this is the part that usually breaks my heart the most.

Anonymous

It’s hard to relate with people’s loss while grieving. People handle grief differently and sometimes, consolatory words are best left unsaid. Just being there for them through it all might be enough.

Ademola Adedoyin

We all would have to grieve someone at a point time. Our expressions may differ but the process almost similar. This was a nice review!

Chimdi

Grief is an inevitable phase we all experience at some point in our life…Thanks for this wonderful review.

Elizabetho

Indeed, “Age is irrelevant in grief, not how but how loved” hopefully we all experience such love while still alive.